The history of manuscripts

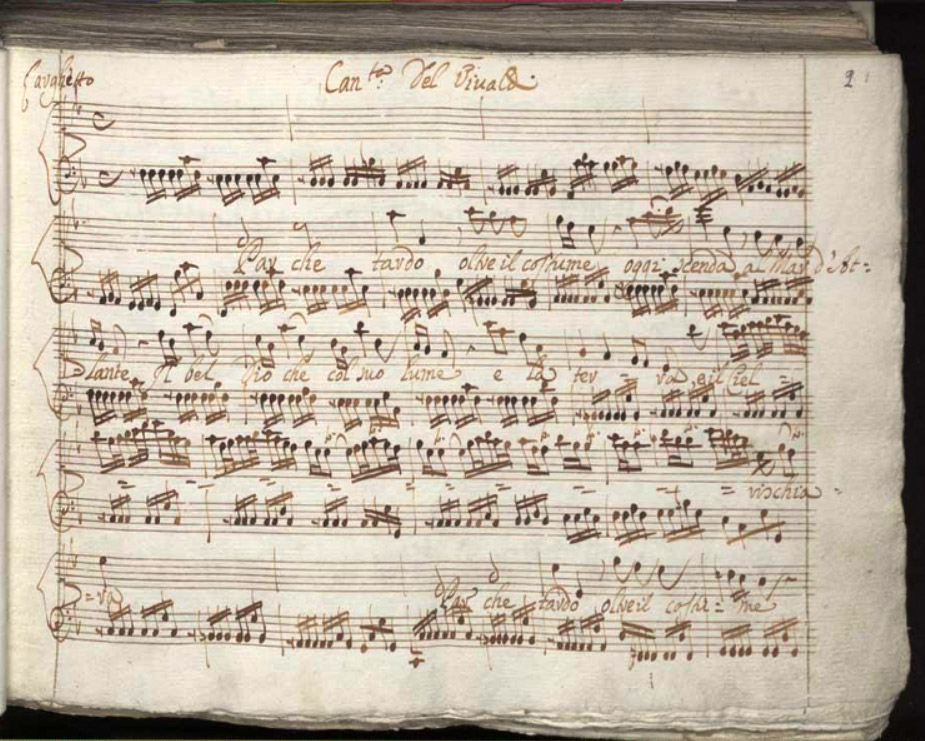

Antonio Vivaldi, “Par che tardo, oltre il costume”. Cantata for soprano and basso continuo. Collection Foà 27, f.2-5. By courtesy of Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo, Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria di Torino. Reproduction prohibited.

Judging by the writings of foreign travelers who have crossed Italy, the city of Turin has passed relatively unnoticed for many centuries. The fame of his opera house, founded in 1740, will consolidate in the second half of the eighteenth century. We are therefore far from the musical sphere of Antonio Vivaldi. Only an anonymous document alludes to his brief stay in this city, as a young man, accompanied by his father, apparently to work with a member of a renowned family of violinists, the Somis. Ironically of fate, Antonio Vivaldi’s personal music library, which accounts for no less than 92% of the composer’s autograph scores today, is now preserved in the National Library of the city of Turin. The fund consists of 450 documents. How this substantial collection arrived in Turin, is in itself a very curious story.

We know from certain sources that in 1745 twenty-seven volumes of the music of the Red Priest were in Venice in the library of a Venetian senator, Count Jacopo Soranzo. It is likely that he bought them from the composer’s brother, Francesco Vivaldi, a Venetian barber and wig, who would inherit them after Antonio’s death in 1741.

The twenty-seven volumes then passed from the hands of Count Soranzo to those of Count Giacomo Durazzo, who kept them in his palace on the Grand Canal until his death. His nephew Girolamo, the last Doge of Genoa, moved them to Genoa where they remained for about a century in the family villa. In 1893, the volumes were divided into equal parts and bequeathed to the brothers, Marcello and Flavio Durazzo. Marcello tied his part to the Salesian College of San Carlo, near Casale Monferrato.

In 1926, the director of the College, wishing to undertake renovation work on the building, decided to sell the volumes. He then contacted the National Library of Turin for an expert opinion. Luigi Torri, the library director, immediately requested the opinion of Alberto Gentili, professor of the history of music at the University of Turin. They both realized the immense value of the collection but neither the library nor the city had sufficient funds to buy it. Gentili therefore turned to Roberto Foà, a friend and wealthy businessman, who bought the volumes in 1927, in memory of his deceased son, and then donated them to the library. However, it was half of the entire Vivaldian legacy. The other half remained in Genoa and it was only after lengthy negotiations that in 1930 the last heirs of the noble family agreed to sell it. The collection was therefore completed, this time thanks to the money of the entrepreneur Filippo Giordano.

And it is just so, for a concatenation of fortuitous events, that the library of the manuscripts of Antonio Vivaldi has found a worthy dwelling within the National Library of Turin, where it is better known as “Fondo Foà – Giordano”. The twenty-seven volumes consist of at least 450 works ranging from single sheet music to full scores of operas. The quantity of instrumental music is very remarkable: 296 concerts for one or more instruments, strings and continuo (including 110 concerts for violin and 39 concerts for bassoon), cantatas, motets and fourteen complete operas.

In 1992, the Istituto per i Beni Musicali in Piemonte, thanks to the musicologist Alberto Basso, undertook the cataloging of the Piedmont music archives. The Institute’s activities will be expanded later when, at the end of the 1990s, Alberto Basso conceived the extraordinary project of recording all the music contained in the manuscripts, thus constituting a discographic collection of Vivaldian autographs. He then turned to the Opus 111 record company (now Naive), which welcomed the idea with enthusiasm. And this is how the Vivaldi Edition began, a co-production directed by these two groups and partially financed by the Piedmont Region, the CRT Foundation (Cassa di Risparmio di Torino) and the Compagnia di San Paolo. Opened in 2000, the project should take around fifteen years.

Only in the late 80s, early 90s, research on performing practices in musical Baroque and the reconstruction of vintage instruments reached such a level that Vivaldi’s music could be interpreted in a completely convincing way. Then Alberto Basso came up with the idea of recording the integral, divided into categories (sacred music, violin concerts, bassoon concerts, etc.). Although this choice may have seemed initially exaggerated and rather monotonous, this rigorous categorization has allowed the public to discover how conspicuous the mass of music composed by the Red Priest is.

The Vivaldi Edition has brought Vivaldi’s manuscripts closer to talented musicians capable of fully grasping the Italian spirit. Among the many illustrious conductors involved in the project it is enough to mention Rinaldo Alessandrini and the Concerto Italiano, Jean-Christophe Spinosi and the Ensemble Matheus, Giovanni Antonini and the Giardino Armonico, Ottavio Dantone with his Accademia Bizantina or Alessandro de Marchi with the Academia Montis Regalis Piedmontese orchestra. The list of eminent instrumentalists includes the cellist Christophe Coin, the bassoonist Sergio Azzolini, the oboist Alfredo Bernardini, the lutenist Rolf Lislevand and many others. The Edition has also proved to be an excellent showcase for renowned singers such as Magdalena Kozena, Sandrine Piau, Marie-Nicole Lemieux, Sara Mingardo, Lorenzo Regazzo, Philippe Jaroussky and Sonia Prina, to name just a few.

If this imposing mass of music could have remained intact in the archives for so long, it is partly due to the observation made by Luigi Dallapiccola, later taken up by Igor Stravinsky, according to which Vivaldi would have composed the same concert hundreds of times. What springs from this recording project is instead the infinite variety of his music. His personal style is certainly easily recognizable but what else is style if not the frame in which Vivaldi has given ample vent to his unlimited creativity? It’s time to find out.